Social Media Marketers Can Learn Lessons from Paul Revere's Ride

Today is a civic holiday in Massachusetts: Patriots’ Day. It commemorates the anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the first battles of the American Revolutionary War. It also offers social media marketers some important lessons that are still relevant today.

Now, all of us have heard about Paul Revere‘s ride. But, did you know that the battle of Lexington was fought in Concord by the men of Acton?

If that’s news to you, I recommend that you read Paul Revere’s Ride (Oxford University Press, 1994) by David Hackett Fischer, which tells a more compelling story than Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem. According to Fischer, Paul Revere was able to spread the alarm so effectively because he had played a key role earlier in the Boston Tea Party. (The original one in 1773.)

Revere was also a member of several clubs in the Boston area, including the London Enemies List, the North Caucus, and the Long Room Club. He also networked socially at two taverns, Cromwell’s Head and Bunch of Grapes. The other members of these clubs and the people who gathered at these taverns were the political leaders who ended up starting the American Revolutionary War in 1775.

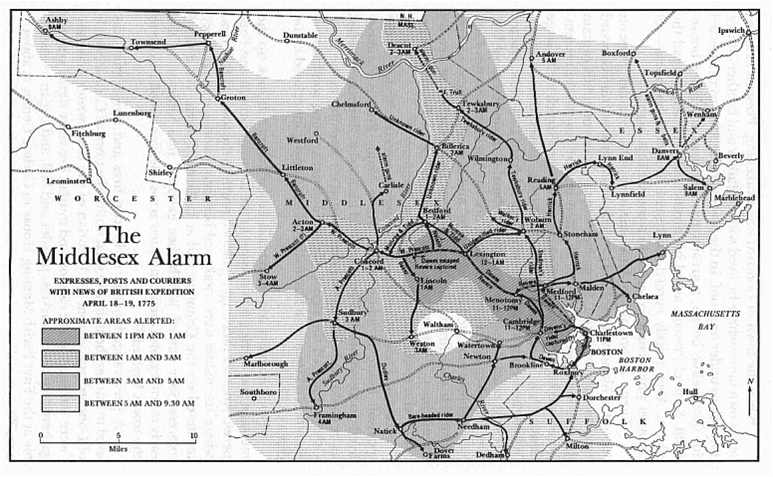

Social media marketers should also take a long look at Fischer’s map of the Middlesex alarm. It is also cited in Diffusion of Innovations (Free Press, 2003) by Everett M. Rogers to illustrate how opinion leaders and diffusion networks work.

As the map below illustrates, as many as 40 riders carried news of the British expedition throughout Middlesex County — a 750-square-mile area — from 11:00 p.m. on April 18 to 9:30 a.m. on April 19, 1775.

Notice that the Waltham militia didn’t join in the fighting, even though Lexington is next door. What happened?

Although Henry Wadsworth Longfellow made it sound like Revere was the only rider that night, there was another: William Dawes, Jr. And Waltham, which was on Dawes’s route, never received an effective alarm.

Rogers explained, “Revere knew exactly which doors to pound on during his ride on Brown Beauty that April night. As a result, he awakened key individuals, who then rallied their neighbors to take up arms against the British.”

He added, “In comparison, Dawes did not know the territory as well as Revere. As he rode through rural Massachusetts on the night of April 18, he simply knocked on random doors. The occupants in most cases simply turned over and went back to sleep.”

It’s also worth noting that neither Revere nor Dawes rode through Acton. On their ride from Lexington to Concord, they met Dr. Samuel Prescott at 1:00 p.m. When

the three arrived near Hartwell’s tavern in Lincoln, they were attacked by four British officers from a scouting party. Revere and Dawes were taken prisoner, but Prescott succeeded in escaping by jumping his horse over a wall. He was the only one of the three men to reach Concord and warn the town.

Prescott then proceeded farther west to warn Acton. He arrived at the Isaac Davis homestead between 2:00 and 3:00 a.m. to alarm the captain of the Acton Minutemen that “the regulars are out!”

In other words, Revere didn’t broadcast his message to every Middlesex village and farm. The message that “the regulars are out” went viral from Revere to Prescott to Davis. And the midnight ride of William Dawes didn’t have the same impact because

he didn’t know the opinion leaders in Waltham and they wouldn’t have known him.

In his book The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (Back Bay Books, 2002), Malcolm Gladwell compares the two alarm riders.

Revere was able to galvanize the colonial minutemen so effectively in part because he was what Gladwell calls a “Connector.” Revere was “the man with the biggest Rolodex in colonial Boston.” He knew just about everybody, particularly the revolutionary leaders in each of the towns that he rode through.

In contrast, Gladwell calls Dawes an “ordinary man.” He wasn’t a “maven” who gathered extensive information about the British, he didn’t know what was going on, and he didn’t know exactly whom to tell.

But what about Prescott?

Prescott was on the road after an evening with his fiancée, Lydia Mulliken. Although Prescott joined Revere and Dawes on their ride from Lexington to Concord, he was an unplanned alarm rider.

When the three were attacked by four British officers, Revere and Dawes were taken prisoner. But Prescott, who had the reins of his horse’s bridle cut, succeeded in making his escape by jumping his horse over a wall.

Prescott was the only one of the three riders to reach Concord and warn the town. And he didn’t stop there. He proceeded further west to warn Acton.

Although his midnight ride to this community was unplanned, Prescott’s reached Captain Davis in time to muster the Acton Minutemen, march to Concord, and engage the British army at the “rude bridge that arched the flood.”

That’s when the tide of battle turned. And that’s why Prescott’s ride is reenacted on Patriots Day eve each year in Acton, the town where I live.

So, social media marketers can learn three key lessons from Paul Revere’s Ride.

First, become a fully vested member of the community.

Second, don’t waste your time knocking on random doors.

Third, ask for help when you engage the community.

Get it? Got it? Good.